The Wrack

The Wrack is the Wells Reserve blog, our collective logbook on the web.

The Wrack is the Wells Reserve blog, our collective logbook on the web.

An oceanographer's ashes will be delivered by sea turtle into the Gulf of Mexico on Saturday. It's a fitting tribute, since the reptilian ash bearer is one of thousands of marine animals the late scientist helped rescue along the Texas coast over the past 38 years.

Tony Amos died September 4, just days after Hurricane Harvey crossed the barrier beaches of the Texas coastal bend and rumbled over the familiar facilities of the University of Texas Marine Science Institute (home of the Mission-Aransas Reserve).

Tony would have been one of the first and best observers to document Harvey's impact on Gulf Coast beaches. He had been studying one 7-mile stretch for almost 40 years, completing close to 6,000 surveys of birds, turtles, and marine debris in that time.

Just a couple of years into his survey effort, an exploratory oil well in the gulf suffered a major blowout. For months afterward, oil flowed from Ixtoc-I at a rate of up to 30,000 barrels a day. An estimated 3 million barrels of oil (126 million gallons) escaped into the water.

Tony watched as the oil floated from Mexico toward the Texas coastline. Wearing his oceanographer's hat at sea, he monitored the creeping oil slicks. Out on his frequent beach surveys, he documented the oil washing ashore and its effects, especially on birds and sea turtles. In 1980, Tony collected his observations for a presentation to the American Ornithologists Union: "Oiling of shorebirds in South Texas following the IXTOC-1 oil spill."

My slender thread of connection to Tony was through the abstract of his talk, which I discovered while perusing the scientific literature after my own run-in with beached oil.

My birding buddy Eric and I had planned a Christmas-break jaunt to the Washington coast, where we would chase merlins, turnstones, surfbirds, and murres. The storms that had been racing in off the Pacific were expected to abate, so we drove out to Grays Harbor and down the Ocean Shores peninsula to begin our search at Point Brown jetty, a shorebird-seabird hot spot apt to turn up our target birds and — you never know — something unexpected.

When we arrived at the jetty the tide was very high. Storm-driven seas thundered into the rocks, throwing water across the jetty and sending salt spray skyward. Clearly, we wouldn't be walking to the tip to scan for pelagics. We were beachbound, but not dissuaded.

My first find was a flock of 25 semipalmated plovers huddled high on the beach out of the wind. One of them threw me. I puzzled over its red-brown belly and splotched sides. Thirteen more plovers flew in, four of them with similar markings. Then my attention shifted to a nearby sandpiper bearing an inexplicable color pattern on its face, breast, and belly. I was struggling to make sense of all the weird birds, when Eric shouted over the wind and waves: "There's oil in the water!"

As if on cue, a city firefighter drove in to check the beach for oil. Openly agitated, he told us an offshore oil barge had been struck by its tow during the night. One of its tanks was gashed. Nobody was sure how much oil might have spilled, or where and when it might come ashore. We had two answers: Here and now.

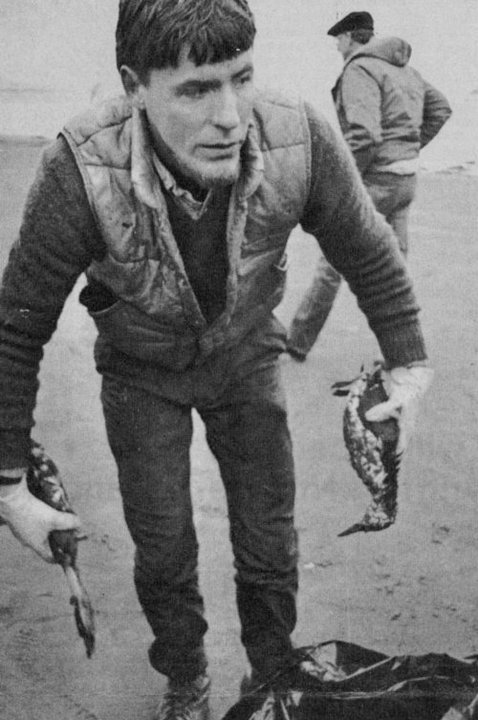

Our birdwatching trip suddenly diverted, Eric and I marched north along the edge of the dune. We encountered thick mats of oil spread across the sand and coagulated gobs of goo littering the beach. And we found oil-soaked seabirds — scoters, murres, grebes — distressed and helplessly out of place.

For the rest of the day, we surveyed nearby beaches for oil and oiled birds, but as light waned and weather deteriorated we set up camp.

Early on Christmas Eve, we were approached by a state wildlife biologist. He asked us to start picking up birds, dead or alive, and handed over a pile of trash bags. We covered a mile in 2 hours, collecting 23 living birds and 7 dead ones, some dripping tar when lifted from the sand. As we delivered our second load at mid day, a flurry of photographers, rescue volunteers, and onlookers surrounded us. The Nestucca spill was news.

Eric and I continued our patrols, surveying flocks of sandpipers and plovers along the way. A disheartening percentage had oil on their feathers, but unlike the seabirds that were soaked by floating oil, most shorebirds showed only patches of oil and remained able to fly. That day we tallied about 1,000 shorebirds with fouled plumage, but picked up none that were dead or incapacitated. At dusk, exhausted and discouraged, we cut our trip short.

We were back at Grays Harbor in a couple of days, reenergized and ready to complete a thorough shorebird survey over 11 miles of beach. Several more times that winter we returned, continuing to document the status of oiled shorebirds.

Eric and I spent months delving into the literature and consulting people who had studied the effects of oil on shorebirds. One of my most anticipated calls was to Tony Amos. Based on his AOU abstract, I was sure he could share additional insights.

On the telephone, with an accent not Texan but British, Tony described subtle bird behaviors and specific vulnerabilities detectable only through careful, habitual observation. Here was an expert with an easy demeanor, a clear communicator with compassion for his study subjects. As an undergraduate doing my first bit of "real science," I was elated to encounter such a receptive ear and open font of shorebird knowledge. Tony gave me a page of notes and new confidence in the importance of our work.

Eric and I published our first scientific paper as a result of that hijacked birding trip, but by the time it appeared in print everyone's oil-spill attention had shifted away, first to the Exxon Valdez (3 months after the Nestucca) and, a year later, to Kuwait. Oil spills. Memories fade.

A quarter century after I closed my Nestucca file, I was surprised to see a short video called "Tony Amos Legacy," winner of the Tidal Award at the 2016 NERRS Film Fest. I learned more of Tony's story and was prompted to look further.

I discovered that Tony, driven by his Ixtoc-I experience, had founded the Animal Rehabilitation Keep (ARK) as a marine animal rescue facility serving the Texas coast. He also wrote hundreds of columns for a Port Aransas newspaper and took every opportunity to cultivate public interest in coastal wildlife. In 2014, he was named Recovery Champion for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service southwest region and in 2015 the Port Aransas city council named a beach in his honor.

Oil spills. Some of us remember. A precious few act to restore some balance.

In Tony's final days, Hurricane Harvey smashed the renamed Amos Rehabilitation Keep. But in his spirit, the Friends of the ARK and Mission-Aransas Reserve have vowed to restore it. To join me in supporting their efforts, please visit the ARK donation page.